Tags

Arts, Celebrity Encounters, Cole Porter, Herbie Hancock, Jesus, johnny mercer, Lorenz Hart, Miscellaneous, music, Nymph Errant

Never accept a favor from someone you find insufferable. Korman was going away for a week and he offered me the use of his sexy two-seater Mazda Miata, while he was gone. Naively, I took him up on it. This was a mistake because now I was obligated to him, and he felt he had the right to commandeer me each evening the minute I got up from the piano. I had a job entertaining, singing Gershwin, Bernstein and Cole Porter at Starr Boggs fancy restaurant in Westhampton Beach. His name was Bob Korman and he wanted desperately to be part of the Musical Theater. He was one of those people who tried to impress you by requesting obscure songs from forgotten musicals: “Can you play His Girl Back Home? You know, the song they cut from South Pacific?” I could. I did. “How about It’s Bad For Me? From Nymph Errant?” I played it. With the verse. There was something seductive about this game, getting the answers right, never letting him stump me. Trouble was, when I got off the stand, he wouldn’t leave me alone. “Got an idea I’d like to discuss with you.” he said one night. “I’m getting the rights to My Man Godfrey,” he told me, naming a classic thirties screwball comedy, “and I think I can interpolate ten Cole Porter songs and make it a musical.” I sighed. It was one of those half-baked ideas that amateurs come up with. You can’t shoe-horn established tunes into a play, it won’t work, it’s like trying to graft an armadillo kidney into a swan.

“I’ve got the filmscript at home and the Porter songbook. Would you come take a look?” Damn, I thought, why did I ever use his stupid Mazda? “See, here where she gets a crush on Godfrey, You’d Be So Easy to Love would fit perfectly. He was like a shy schoolkid, seeking teacher’s approval. “Except, Bob,” I countered, “at the end of the song she says It does seem a shame/That you can’t see/Your future with me.” Korman’s face fell. “You think that invalidates the idea?” “Unless you want to re-write the lyric.” “No, no, I don’t want to touch the lyrics.” “You could try You Do Something to Me in that spot.” I offered, and immediately regretted abetting the idea of this dumb project. It would still come out like Frankenstein’s monster, forced and lifeless. And, just to make matters even more fun, in addition to his amateurishness and his insistent pushiness, Bob was a drinker. By the end of the any given evening he was close to falling-down sloshed. In fact, he’d run his lovely little Mazda into a tree one night, heading home. The cops had given him a summons and he’d had to pay a stiff fine.  Still and all, I couldn’t entirely dislike him. He was so earnest in his desire to make a contribution to musicals –and, of course, this was my obsession as well. I wanted to create original shows. So, in a way, we were bonded. And then one night Herby the lawyer came into Starr’s with his trumpet and set off an incident. Herby Westheimer was a personal injury lawyer. He had a pronounced Brooklyn accent and a wife to match, Gloria, with big, dark bouffant hair and long, blood-red nails. In his youth, Herby had been a club- date musician, and he wondered could he bring in his instrument? “Maybe I could sit in for a few tunes?” “Sure,” I said, “what do you like to play?” “It Hadda Be You,” said Herby, “Original is G,” he said.

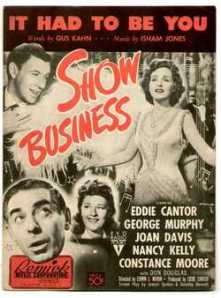

Still and all, I couldn’t entirely dislike him. He was so earnest in his desire to make a contribution to musicals –and, of course, this was my obsession as well. I wanted to create original shows. So, in a way, we were bonded. And then one night Herby the lawyer came into Starr’s with his trumpet and set off an incident. Herby Westheimer was a personal injury lawyer. He had a pronounced Brooklyn accent and a wife to match, Gloria, with big, dark bouffant hair and long, blood-red nails. In his youth, Herby had been a club- date musician, and he wondered could he bring in his instrument? “Maybe I could sit in for a few tunes?” “Sure,” I said, “what do you like to play?” “It Hadda Be You,” said Herby, “Original is G,” he said.

I gave him a four bar intro, and he swung into this great, well-known standard, one of the songs my friend Margaret Whiting referred to as an Ah Tune –when the audience hears the first few bars, they go Ahh. At his table, I saw Korman wince. This selection was too plebeian for him, not from a show, just a pop tune, and not even by one of the great composers like Porter, Gershwin or Rodgers. Herby played just like his persona: loud and buoyant, without subtlety, hitting a clinker now and then, boisterously good natured, having a great time. He loved the music.

I gave him a four bar intro, and he swung into this great, well-known standard, one of the songs my friend Margaret Whiting referred to as an Ah Tune –when the audience hears the first few bars, they go Ahh. At his table, I saw Korman wince. This selection was too plebeian for him, not from a show, just a pop tune, and not even by one of the great composers like Porter, Gershwin or Rodgers. Herby played just like his persona: loud and buoyant, without subtlety, hitting a clinker now and then, boisterously good natured, having a great time. He loved the music.

Well, this display infuriated Bob, who was already onto his fourth drink. He waved at Herby disparagingly, impatiently. “Sit down!” he cried. “Let John sing.” Because, in an effort to showcase Herby, I’d left out my vocals…to let his trumpet take center stage. I was having fun, listening to Herby and his bumptious, innocent style. The customers loved it when an impromptu performance like this happened. Gloria, the bouffant wife, was beaming. It was a good exercise for me to play familiar tunes in unfamiliar keys. But Korman was glowering into his glass. “Jesus,” he muttered, “the people they let in here.” He rose and confronted Herby, weaving slightly. “You’ve gotta stop that.” he told him, “it ruins the songs.” “Who are you?” Herby asked him. “John’s here to play showtunes,” Korman continued. “He doesn’t need any trumpet. Let him sing the lyric.” “Nobody’s stopping him,” Herby countered. Bob stumbled back to his table and finished his fifth drink. Herby wanted to play I’m Gonna Sit Right Down and Write Myself a Letter. “Original’s C.” he informed me. But suddenly, Korman was back: “You gotta stop it—“ he muttered, and simultaneously put his hands on the bell of Herby’s horn and gave an ineffective yank. Herby tightened his grip, Bob yanked again and suddenly an insane struggle erupted in the midst of the dining room. Bob, holding the trumpet in one hand, took an ineffective swing at Herby with the other. Heads turned, forks dropped. Herby gave Klineman a shove and sent him crashing into a table of four near the piano. “Jesus—“ someone said, and I rose from the keyboard and grabbed Korman. “Hey, Bob,” I said, seizing him by the shoulders, “you don’t want to do that.” I walked him firmly back to his table. “I’ll sing the lyrics, okay?” Bob’s eyes filled with tears. “Without the lyrics, you’re only getting half the song…” he said. “I mean, Johnny Mercer, Lorenz Hart, Jesus…” In that moment, my heart went out to him; he cared so very deeply, and he was never going to be part of it. All that week, the incident haunted me. The following Friday the jitney dropped me off in Westhampton Beach…and Korman was waiting for me. “John,” he said, “you’ve got to help me. Look:” He proffered a letter. It was from a Herby’s office in Brooklyn –and it was a summons: you are hereby ordered to appear November 20th to answer charges of assault against the plaintiff, Herb Westheimer. If convicted, the summons continued, Herby was requesting damages of one hundred and twenty million dollars –plus court costs! In addition to quoting this outrageous sum, the summons had to be answered in a courtroom in Staten Island. On November 20th, three weeks from now. Klineman was staring at me helplessly. “What am I gonna do, John?” “I dunno, Bob,” I countered. “I guess you’ll have to appear.” He put his hand on my wrist: “Would you talk to him?” I had no idea what to say. “I’ll think about it,” I finally managed. That night, Herby and Gloria came in and I sat with them. Gloria couldn’t stop talking about what a jerk Korman was. Herby smiled. “Did he get my letter?” “Did he get it?? I said, “he’s practically under the table!” “Yeah, well he’s got to learn he can’t act that way,” said the lawyer; “I decided to teach him a lesson.” “Herby,” I asked him, “you’re asking for a hundred twenty million, right?” Herby smiled. “Would you settle for sixty?” I inquired. Herby’s grin got wider. “Tell him to write me a letter of apology –and make it sincere.” And you know what? Korman, so relieved that Herby wasn’t going through with the suit, wrote the most profound and beautiful letter. Whew.

“Would you settle for sixty?” Another entertaining and moving entry – thank you! You always find the humanity.

John, what a wonderful story. Thank you.

Hi John,

I;m going to give you a call tomorrow or Tuesday re this post.

Love to you and Suzanne Bobbie

From: John Meyer Reply-To: John Meyer Date: Saturday, September 8, 2012 5:58 PM To: bobbie horowitz Subject: [New post] Klineman the Purist and Horn-Man Herby

WordPress.com meyerwire posted: ” Never accept a favor from someone you find insufferable. Klineman was going away for a week and he offered me the use of his sexy two-seater Mazda Miata, while he was gone. Naively, I took him up on it. This was a mistake because now I was obligated t”

Thanks Nanci, Maureen and Bobbie -it’s wonderful to get your responses. Keep ’em coming.